|

0 Comments

“Without imperfection, neither you nor I would exist.” ~ Stephen Hawking The politicians, pundits and journalists who are against the Iran Nuclear Agreement focus on one point: it’s not perfect and could be better. Most of us know from experience that humans are not perfect. Isn’t it unrealistic to expect that any agreement created by imperfect beings be perfect? We are not in a position to force capitulation. Negotiation is a process that creates a path forward in which each party retains its dignity, propelled by the desire to give up something of personal value in order to gain something of greater value for everyone. Agreements are never perfect. If Congress thwarts this agreement, what are the alternatives? We could continue and even increase sanctions, but our allies will not stand by our side, and if we are the only country applying sanctions the effects will be minimal—not a perfect alternative. Fifty years of embargoing and sanctioning Cuba has shown us that these alternatives can and will cause increased defiance. We imposed strict sanctions on Russia, yet Putin doesn’t seem a bit inclined to return Crimea. We could also go to war, but we all know how imperfect war is. We only have to look at recent history to remember that in modern war there is seldom a clear winner and the costs are staggering and tragic. Consider: Korean War: No winner emerged. Instead, Korea remains divided and the North retains the capability of making a nuclear bomb(s). The war was waged at a great cost in terms of money and lives. Vietnam War: Objectively, North Vietnam, the communists, achieved their goals of reuniting and gaining independence for the whole of Vietnam, and it remains under communist rule today. The U.S. dropped more than 7 million tons of bombs—more than twice the amount that was dropped on Europe and Asia in World War II—and we lost more than 58,000 young lives. Not a perfect solution or result. Gulf War: The aftermath of the Persian Gulf War appeared to be a victory, but what we learned is that the victory was hollow. Saddam Hussein was not forced from power and the region became less stable. Many believe that this war helped to make Al Qaeda a force that would later strike our homeland. Iraq War: The initial stage of the war was a raging success—the banner proclaimed “Mission Accomplished.” Yet, the war created eight years of sectarian violence, 4,900 American lives lost and many more severely injured, and it amounted to a trillion dollar debt from which we still haven’t recovered. Iraq is still incapable of defending itself, and it gave rise to ISIS. We need to ask ourselves if an imperfect agreement that may produce peace and diminish the potential of a nuclear Middle East is a better risk than the alternatives. Or are we willing to put our country and the world at risk by pursuing alternatives that have a dismal and tragic record. Can we afford to risk isolating ourselves from our allies, countries critical to solving the world’s most urgent problems? Are we willing to once again shed the blood of our youth by waging war? Writer Archibald McLeish said, “There is only one thing more painful than learning from experience and that is not learning from experience.” We have a clear choice. The Iran Nuclear Agreement has risks, but experience has shown that the alternatives are much more costly in terms of world standing, capital and human lives. All our options are imperfect and risky, but the greater risk here is repeating the past when we have a chance to take a risk for peace instead.  I can’t seem to get through a page of John Gardner’s book Self-Renewal: The Individual and the Innovative Society—which is full of lessons, advice and wisdom on the nature and nurturing of self-renewal—without being struck by a concept that resonates deeply. The following is just one example: “For every citizen movement that changes the course of history, there are many thousands that hardly create a ripple. The few movements that survive are those that speak to the authentic concerns of substantial numbers of people.” Immediately, names like Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Susan B. Anthony, and Harvey Milk come to mind. These individuals were able to profoundly articulate the authentic human and civil rights concerns of millions of disaffected people, and because of this they became leaders within movements that changed societies. The ability to sense, understand and authentically communicate the concerns of others is the core of leadership, and it’s as important in leading organizations as it is in large-scale societal change, because at the heart of all workplaces are people with concerns. An alternative perspective on engagement Organizations that achieve high levels of employee engagement experience superior results in many critical performance and success metrics, including revenue. And yet for many leaders, engendering deep levels of stakeholder engagement appears to be a difficult challenge. Too often I’ve heard leadership teams, when considering an engagement effort, say, “You can never satisfy them; if we change, they’ll only find something else to complain about.” This perspective of engagement, about giving in or giving up something, is a formula for failure. An alternative perspective that I recommend to leaders is to frame engagement as a “concern movement”: a process of recognizing and attending to the mutual concerns of both management and employees. The foundation of a concern movement In his book Moral Courage, Rushworth Kidder identifies the values of honesty, responsibility, respect, fairness, and compassion as core human values. The foundation of a concern movement starts with a focus on these five universally accepted values, which, when invoked and practiced by leaders, speak to the essence of human concerns. Honesty, responsibility, respect, fairness, and compassion transcend all cultural and organizational demographics. When they flourish, so does human engagement. To build a culture of engagement, organizations must integrate these values into the “why” and “how” they lead and the structures and systems of their operation. This approach doesn’t require a leader to be a great orator, or to risks one’s safety for a movement—but it does require that you recognize and understand your stakeholders’ concerns and to be able to authentically resonate with their concerns. Values are the powerful “why” that influence what people do and how they do it. Try delivering bad news to your organization without respect and compassion; it will inflame passions, kill engagement, or both. When employees perceive their organization to have a disregard for basic human values, it takes a toll on organizational results. On the other hand, the benefits of employee engagement are well documented, and the road to engagement is paved with core human values. Organizations willing to walk the walk and talk the talk and start their own concern movement will succeed—both personally and as a whole. I have a theory about values, leadership, and workforce engagement that is related to a study I read on brain imagining and sacred values. The study, titled, “The Price of Your Soul: Neural evidence for the non-utilitarian representation of sacred values,” was conducted by Gregory Burns, PhD, Director of the Center for Neuropolicy at Emory University. Through the study Burns found that “sacred values prompt greater activation of an area of the brain associated with rules-based, right-or-wrong thought processes as opposed to the regions linked to processing of costs-versus-benefits."

The study gave participants an option to disavow any of their personal value statements for money. Disavowing a statement meant they could receive as much as $100 by simply agreeing to sign a document stating the opposite of what they said they believed. The disavowing was interpreted as the value statement not being sacred to the person. Statements that the participants refused to disavow were classified as being personally sacred. Brain imaging indicated that scared and non-sacred values activated different areas of the brain. The scared values activated areas associated with right and wrong and the non-sacred values activated areas related to pleasure and rewards. In addition, the researchers found that the amygdala region became activated when a person’s sacred values were challenged. The amygdala is the part of the brain that controls our “911” stress alert reactions of fight, flee or freeze when it perceives a threat to our well-being. It is also associated with our emotions, particularly emotions connected to perceived negative experiences, which over time creates a filing cabinet of negative memories. In our modern world people usually don’t react physically by fighting or fleeing, they react emotionally. We fight by arguing or being stubborn; we flee by disengagingmentally and emotionally, which lessens commitment; and we freeze by shutting down our creativity. It is emotional reactions like these with which a leader must contend. Therefore, developing one’s emotional intelligence is critical to effectively counter and minimize these stress responses. Organizations would be wise to establish emotional intelligence as a leadership prerequisite if they want to reap the benefit from higher levels of workforce engagement I believe that workforce engagement issues are a result of leaders and organizations not operating from a foundation of sacred values. The Institute for Global Ethics did exhaustive surveying and research in an attempt to identify what core moral and ethical values were held in highest regard by people and communities throughout the world. No matter where they went, they found the same answers: honesty, responsibility, respect, fairness, and compassion. In essence, these are core sacred values. Applying the brain imaging research from the sacred values study, it would seem that if any of these five core values were in essence disavowed by anyone – in this instance, a leader – it would activate the “right and wrong” areas in the brains of his or her employees and at the same time activate their amygdale, putting each into either a fight, freeze or flee state of reaction. The result could be a strong feeling on part of an employee to not trust this person and to feel that they have been “wronged,” both of which will negatively impact engagement, commitment, performance, and most importantly, trust. Values authenticity is the core issue. Leaders and organizations who – within their heart, head, and gut – are not authentically aligned and committed to these core sacred values will never be able to fully capture the hearts and minds of their workforce nor their stakeholders. The Gallup Organization, which has made a science of employee engagement, reported that in the third quarter of 2011, “Seventy-one percent of American workers are ‘not engaged’ or ‘actively disengaged’ in their work, meaning they are emotionally disconnected from their workplaces and are less likely to be productive.” This means that 71% of the country’s workforce is emotionally reacting by fighting, fleeing or freezing.Why? Because they believe that their sacred values are absent or being disavowed. A leader cannot drive workforce engagement if he or she does not authentically hold these five core values as sacred. When I’ve had the opportunity to talk, or should I say listen, to employees, these five values are at the core of their concerns and issues, and are the crux of their disengagement:

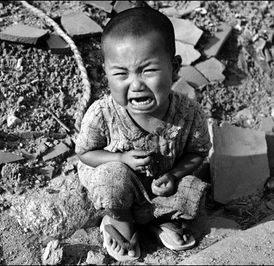

These same sacred values are at the heart of the issues that are polarizing and creating conflict in this country and around the world and thwarting people from finding solutions to their most pressing problems:

Leaders from all sectors of our society must develop a deeper understanding and sensitivity of how these core sacred values dynamically hold relationships, teams, organizations, and countries together, all be it sometimes in a chaotic way. When organizational and political leaders focus on and subscribe to the perspective of cost versus benefit, there undoubtedly will be tension and that tension will give rise to conflict and disengagement. In his book Moral Courage, Rushworth Kidder states, “Successful organizations must require moral courage in their leaders and then work assiduously that it is rarely needed.” I agree, but more importantly leaders must take on the hard work – the work of authentically committing to these sacred core values and then modeling moral courage when they are challenged. To create a highly engaged workforce leaders and organizations would be better served to first look in-ward and to evaluate the depth of their commitment to these core sacred values. Authenticity and Moral Courage are two of the Seven Hallmarks of Relationship–Centered Leadership. If you have an interest in building workforce engagement and becoming a high-performing leader, we invite you to explore the Relationship–Centered Leadership program. For more information on this program download a description from the Free Downloads tab |

Follow us

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed