|

0 Comments

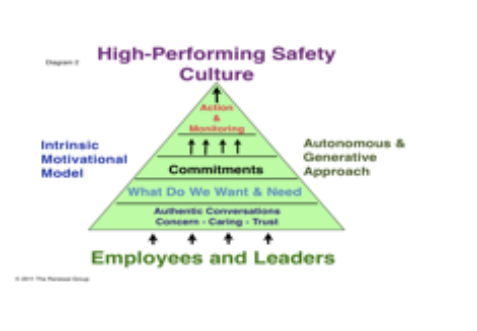

Normally, you assess an organization’s safety culture by observing how employees translate the company’s principles, values, attitudes, and goals into their behavior and decision-making. This seems like a pretty straightforward method, but beware of drawing conclusions based only on observations—you’ll fall into the assumptions trap. I’ve fallen into this myself by relying on direct observations and reports consisting of data based on observations, and I suspect I am not alone. The assumptions trap is a consequence of the way in which the human brain forms patterns to help us manage a complicated life more efficiently. Patterns feed our assumptions. They help us react, predict and make decisions regarding situations without having to assemble and sift through all of the details of what we are observing. The problem is the brain has no investment in making distinctions between fact and fiction. It takes in what it sees, dismisses what doesn’t fit, and draws a conclusion as expeditiously as possible. It will even add in data to fill any gaps just to complete the picture to fit the established pattern. This works very well when we need to slam on the brakes to avoid a child who darts into the road. However, this process has limits when used exclusively to assess or make assumptions about the effectiveness of a safety culture. David McLean, Chief Operating Officer for Maersk, expressed this realization in his article “The Importance Of Process Safety & Promoting A Culture of PSM.” “We were all very good at measuring personal safety performance, i.e. slips, trips, and falls, and this is very tangible, but did a good personal safety record mean we had a safe operation? Clearly not, as several major accidents had proven.” Avoid the Assumptions Trap by Engaging in Conversations “Can you hear me now?” was the key refrain from a Verizon commercial a few years ago. If you listen, you can hear employees using this same refrain in regard to their relationship with their managers. “They never listen to us, and when they do, they don’t hear what we are saying,” I’ve heard employees say. “They already have their minds made up.” Consider for a moment that managers spend 75% to 90% of their time in conversations! Who are they having these conversations with? And are they really listening or just filling in the gaps of existing beliefs and patterns? To understand and know one’s culture you must listen to it—not just to the words but also to the emotional texture of the words. A safety culture is created, nurtured and sustained by the breath and quality of the conversations that take place and the ones that don’t. “What people say and what they withhold matters,” said David Arella, founder and CEO of 4Spires. “Language trumps control. How the communication is initiated and conducted is often more important than what is communicated. An organization is a network of person-to-person work conversations during which information and energy is exchanged. Like cells in your body, the quality of these work-atoms determines the effectiveness of the whole. Attending to and influencing work conversations can help transform culture and improve collaboration.” The true nature of a culture is revealed through its conversations. If you want to understand your culture before making assumptions about your culture’s strengths and weaknesses—what motivates employees and what’s in their hearts and minds—you must engage in open and honest talk. Conversations can help give meaning to observations. Culture is made up of layers of conversations that are constantly vibrating and emitting information. Learning to notice and listen to these waves of information is a critical culture competency. It requires that leaders be committed to moving through the casual and superficial noise in order to gain insight into the organization’s authentic culture and discern what is really motivating employee performance. Don’t Use Data: How to assess your safety culture more effectively Edgar H. Schein, PhD, considered to be one of the foremost experts on organizational culture, believes that if you want to access your organization’s culture, bring together a group of employees who represent each part of the organization and provide an opportunity for them to dialogue about their issues, concerns, and the strengths and weaknesses they experience and perceive in the safety culture. Here is a simple but effective model to help organizations assess and transform their safety culture. It calls for leaders, managers, supervisors, and employees to engage in authentic conversations in which each can express and share their concerns and build the trust required to move forward. Leaders frequently expressed that they had reservations about engaging in these conversations, particularly those that reached below the surface. They preferred to use a survey (hard data). But after working with this model, not only did they obtain the data they wanted; they gained the commitment they needed from employees to work toward common goals. The following questions can help assess if your have a culture that values conversations or if it is reliant on assumptions and patterns. · Is it like pulling teeth to get employees to talk in meetings? · How often do safety leaders practice walking and talking about the site? · Is the word stupid—or a similar insult—ever used to describe safety incidents or the employee involved? · What emotion(s) best describes the mood of the safety culture? Frustration, boredom, disappointment—or excitement, curiosity, and passion? · Do managers abhor meetings and feel that they are a waste of time? · How often have employee safety recommendations been implemented? This self-assessment will begin to give you an indication if the conditions of your safety culture are conducive to meaningful dialogue; if it encourages open and honest conversations or stifles it. A word of caution though: Just because employees may be reluctant to engage in conversations doesn’t mean they don’t want to be heard. Their behavior may be more about their lack of trust, fear of blame, or a result of previous conversations that resulted in a negative experience. A positive safety culture is a repeatedly observant one, not just of behavior but also of its tone and content. Safety leaders would be well served to develop a practice of deeply listening and observing before making assessments and judgments. Contact Tom Wojick for more information on how to introduce conversations into your culture 401-525-0309 [email protected] Emotions and Culture – Drivers of Human Behavior " I can't say I'm sorry enough. I'm sure I'll be criticized, but it's true. I felt awful. It wasn't my intention. […] It's not what I wanted to see or anyone to see." These are the words of Shawn Thornton, a professional hockey player for the Boston Bruins, after attacking and injuring an opponent during a recent game. Suspended by the National Hockey League as punishment for his behavior, the consequences of Thornton’s actions affect him and his team. Why did Thornton attack his opponent in the first place? Based on his response—“It wasn’t my intention”—I suspect he allowed his emotions to take over. In other words, he was “emotionally hijacked.” We’ve all had experiences of being emotionally hijacked, when strong emotions suddenly wield control of our behavior. Our response after the episode is usually the same as his, too: “I don’t know why I acted that way.” Intense emotions can dominate our thinking and drive our actions—they are powerful sources of energy. In emergency or crisis situations, they work to keep us out of harm’s way: Fight, freeze, or flee. But in other, less noble situations, they cause us to react in ways we later regret (“I felt awful”). Having the emotional awareness and insight to prevent or short circuit the hijacking process brought on by intense emotions is called emotional intelligence, a necessity in a world filled with situations that can easily give rise to intense emotions. Carefully handling strong emotions, rather than quickly giving into them, is critical in making reasoned decisions that work for us rather than against us. I also believe an even more powerful force than emotions was involved in Thornton’s reaction that night, a force that oftentimes makes it difficult for individuals to navigate situations that ignite intense emotions: culture. Suppose you are in a business meeting when a colleague pokes fun at your presentation. His comments are humorous but rude and uncaring. You might notice your muscles tensing and your mind racing. Will you walk over and throw your morning coffee in his face (fight)? Excuse yourself and leave the room (flee)? Or stand motionless, unable to respond (freeze)? Since most office business cultures do not encourage, support, or condone physical attacks, you opt not to throw your coffee. What you decide to do instead is respond in an emotionally intelligent way: “Your comments leave me feeling put down and I’m not sure how they have contributed to helping us find a solution. In the future, it would be helpful for me if you could be more specific and constructive with you comments and feedback.” Thornton’s attack took place in a business environment, or culture—professional hockey—that encourages, condones, and supports fighting as a means of solving disputes. For many years, hockey teams employed players for their fighting skills rather than their athletic abilities, according to Seth Wickersham in his article “Fighting the Goon Fight.” It was the role of these enforcers to protect their team’s star players from opponent harassment while also goading the opponent’s star players into a fight. Ben Livingston, a sports journalist, supports this theory in his article “The Bizarre Culture of Hockey.” “The only constant in fighting is that you are assessed a penalty for doing it,” he writes. “There exists a bizarre practice of allowing fighting to occur, while at the same time penalizing the participants for doing it. This has lead to it being called a ‘semi-legal’ practice.” Another potent factor in becoming emotionally hijacked - The emotions of others. In Thornton’s case, this meant the taunting and yelling stirred up by his fans. When a fight breaks out in hockey, fans cheer furiously for someone to be physically punished. Many, in fact, are drawn to the sport for its violence. Though Thornton was penalized for his part in the incident, his co-conspirators—the fans and the culture of professional hockey—escaped without penalty. As in any emotionally intense situation, Thornton’s behavior was the tip of the iceberg. It is the stronger influences and motivators—those that support and permit transgressions like his—that remain below the surface, where the culture of hockey exists. Rules and regulations are never a primary factor in human behavior unless they are in full alignment with a culture’s mission, values and strategic objectives. Rules merely provide cover for an organization so they can identify and blame transgressors and escape accountability and culpability. We’ve seen this with the likes of Enron, British Petroleum (BP), Massey Mines and most recently, the world’s major banks. All professed to be motivated by high ethical standards and comprehensive safety rules and regulations, but the cultures that have dominated these businesses runs contrary to their hollow words. It is emotions and culture that have the greatest effect on human behavior and any organization that attempts to influence and enforce positive behavior with regulations alone will remain vulnerable to disruption, loss, and plenty of emotional hijacking. Thornton said, ”I can’t say I’m sorry enough,” but the burden and responsibility of his actions do not sit entirely on his shoulders. It’s difficult for any employee to make the “right” choices when organizational rules give direction but the culture of the organization is ambiguous about enforcement and in some cases turns a blind eye to negative or unsafe behavior because it supports the organization’s explicit desire for profit, production, entertainment, and risk taking. The NHL, in which fisticuffs remain an integral part of the sport’s culture, penalizes individuals for fighting, but the behavior of its players remains unchanged, because below the surface enforcers are rewarded and celebrated for their transgressions by fans, teammates, and the media. Banks will not change their culture of risk taking for profits when CEO’s get bonuses and salary increments after being penalized billions of dollars for violating regulations. And safety will always be secondary when employees are pushed to keep production up at all costs. The unfortunate aspect of these “Trojan Horse Cultures” is that they present and say one thing, but inside, where true culture resides, are the drivers of behavior, which often put their employees at the lower rungs of the organization in harms way as they attempt to navigate between the rules and what the culture is condoning and endorsing. I’ve worked for the past ten years assisting organizations in identifying where there is culture misalignment and working with them to restore and or build cultures that authentically and consistently align with their mission, values and strategic objectives. The work is hard, but the rewards are significant and produce results that are sustainable and profitable. Most importantly, they become organizations in which leaders and employees feel pride, take ownership and work jointly to insure success, and where leaders and employees feel accountable and safe in stating. “I can’t say I’m sorry enough.”  Which side of the divide are you on - are you a We or They? The they’s and we’s have been at odds before the Hatfields and McCoys starting shooting at each other. The We–They Divide is not unique or new. It has existed since the dawn of employee-manager relationships and to this day it continues to infect, constrain, and confound organizations and leaders. The impact of the We–They Divide on an organization is similar to any infection: Inevitably, it takes a toll on everyone. It diminishes work efficiency, quality, and organizational resilience, and can be the difference between success and failure.

The divide is not just an employee satisfaction or morale issue, though; it strikes at an organization’s bottom line. Towers Perrin’s 2008 Global Workforce study found that We–They Divides have negative consequences on operating margins, but, conversely, if a divide is reduced it can improve an organization’s bottom line. With all the financial, quality, performance, safety, and competitive risks this kind of divide exposes an organization to, and with all the research that validates its existence, why do organizational leaders continue to underestimate its impact? For many, the We–They Divide is untraveled territory with few or trusted maps available to assist them in navigating their way. Traditional organizational constraints like limited financial resources are issues most leaders feel equipped to handle. They can close gaps by reducing or cutting expenses, look for additional financing, or increase revenue by reaching more customers or raising prices. When it comes to the We–They Divide, the solutions are less formulaic. Feeling less confident, lacking in experience, and without training in how to recognize and approach the issue, many leaders are slow to address divides in their workplace. One manager explained to me, “We have only one chance to get this right, therefore we need to go slow.” While slow approaches usually indicate thoughtfulness and precision, in this case it indicates a lack of experience, confidence, and trust. The manager’s adherence to a slow approach only increases the chances that his workplace’s infection of disconnection will spread and widen the divide, making treatment that much more difficult. Employees are more concerned about serious commitments to address the We – They Divide than they are of mistakes. What Is the We–They Divide and the Reality of Perception The Conference Board, a global, independent business membership and research organization working in the public interest since 1916, developed a definition for a concept called employee engagement, which describes the degree of emotional and intellectual connection or disconnection an employee has for his/her job, organization, manager, and coworkers that, in turn, influences and motivates him/her to give and apply additional discretionary effort to his/her work. The We–They Divide is the emotional and intellectual distance between leaders and employees—it is the degree of disconnect. Human behavior is based on perception. Therefore, whether correct or incorrect, fair or unfair, perceptions are each person’s (group’s) reality, and it is these perceptions that create the divide: We Perceptions vs. They Perceptions. Our perceptions create a set of default assumptions that remain the undercurrent of our thoughts and feelings regarding any given topic. A common perception I hear from employees concerns the “invisibility of leaders.” It sounds like this: “We never see him. The only time he leaves his office is when something negative happens. Then he’s in our face wanting answers.” It’s not difficult to predict the assumptions that could arise from this type of perception. While some employees might assume their leader doesn’t care about them, others might assume you only receive attention when you do something wrong. The worst? Some might believe their leader thinks he or she is too good to associate with them. Sadly, most leaders are taken aback to hear of their employees’ assumptions. “I never knew.” While some immediately commit to change, others start explaining, defending, and offering examples of employee engagement. The space between these two perceptions is another example of the We–They Divide. Though some believe they cannot control what others think and assume, and that “no matter what is done employees will always find something else to complain about,” we know this not to be the case. There are a number of methods and approaches that leaders and organizations can take to reduce divide. There are six We -They Divide Prevention Measures leaders can take to positively influence employee perceptions and assumptions that will prevent the divide from widening—and even begin to reduce it. However, it does takes a much more comprehensive initiative to transform a We–They Culture in which employee disengagement is a serious impediment and threat to an organization’s optimal performance to a We Culture. For insight how a client organization accomplished this read, Leaders Don't Motivate - They Create The Conditions For Self-Motivation on this site. The following are We–They Divide Prevention Measures taught by Nicole Gravina, Ph.D. When leaders integrate and apply these concepts while making decisions, communicating with employees, designing systems/processes, and working with each other, they can minimize the perception of the divide and increase cooperation and commitment from employees. Proximity: Employees take particular notice if leaders are in close proximity or if they are distant, and the perception of distance increases the divide. Therefore, a lack of physical, social, and emotional presence by a leader contributes to negative perceptions and assumptions in the We–They Divide. Communicating primarily by email, not attending or holding employee meetings and the absence of informal social contact in meetings, and being absent at informal and formal social events can all contribute to the perception that a leader doesn’t like us, care about us, or understand us. Leaders must be proactive in their efforts to finding ways to bring themselves into closer proximity with their employees. If your office is distant from the people you manage, schedule time on a regular basis to leave your office and meaningfully interact with your employees in their space. Take time to learn about their social and family situations. Engage on a social level. Similarity: is to work against the common perception that leaders are better and more privileged than their hourly workforce. Employees understand that leaders are paid differently and have additional benefits, but they don’t like when their leaders present themselves as better, smarter, wiser, or more privileged. The more you can emphasize your common human similarities, the closer a connection (emotional proximity) will be between a leader and his/her employees. Though you may be fortunate enough to rise on the corporate ladder, never lose sight of where you came from and the people who helped you climb that ladder along the way. Much to their disadvantage, leaders operate in bubbles and cast long shadows. Seldom do they receive unvarnished feedback, which they need in order to understand employee perceptions and behavior. To be an effective leader, one must create opportunities and structural mechanisms that allow for unfiltered feedback. Inconsistent Application of Rules and Policies: Nothing is more irritating to employees—or sends the “I’m better” message—than when leaders excuse themselves from basic workplace policies. Management should always demonstrate its similarity and commitment by adhering to its own rules. Opposing Goals: Are the goals established in various areas of the organization interdependent or independent of the organization’s overarching mission? I have seen incentive structures for a sales groups conflict with the corporate responsibility and quality departments, and instances when safety procedures and goals in a manufacturing organization are not followed because they would have interrupted production goals. Is your team aligned? Differences in Availability of Resources, Time, Feedback, and Recognition: Everyone notices if someone else gets more than they do. If you had brothers or sisters, you know what I mean. Leaders need to be attentive to this aspect of human nature. If an employee or a group of employees perceives that someone is getting more than they are, not only will they think this it unfair, they’ll also feel less important. I’m not simply referring to hard resources like money and equipment, but the softer and less tangible resources such as demonstrations of appreciation and recognition. Though many leaders don’t value recognition as a resource, employees do. Leaders who understand and develop a practice of appreciation and recognition are providing employees with emotional and psychological resources that will motivate and strengthen their commitment for years to come. Lack of Information and Follow-Through: Assuming people know and understand your intentions and your purpose, and that of the organization, is a mistake. Communicate, communicate, and communicate more. Leaders must set a goal to actively communicate and solicit feedback from employees and not stop until you hear, “You’re killing us with all this communication!” Once you hear this statement, you’ll know you’re on the right track. Follow-through is the period at the end of a sentence. One of the downfalls of employee suggestion programs is that employees seldom get feedback or follow-through on the status of their suggestion. Employees will hang onto an issue until they feel the loop has been closed, leaders must follow through, which in turn builds trust. A colleague of mine, Richard Hews, instructs managers on the “Cycle of Commitment or Promise. One of the essential aspects or steps in the cycle is the declared satisfaction. It is here where the initiator and the performer declare their satisfaction if the request was completed to the requirements. Punishment-Oriented Culture: Nothing is more destructive than a culture in which a hammer is the primary leadership tool and every employee feels like a nail. It is divisive, creates aggression, and kills engagement. No high-performance culture is built on a foundation of punishment. This type of culture only exacerbates the We–They Divide, turning it into a chasm. Summary The We–They Divide is a silent and serious threat that can strike the bottom line of an organization and jeopardize its stability and competitiveness. Disaffected and disengaged employees lack the commitment, creativity, and energy to give their discretionary effort. And in a continuously changing and challenging global marketplace that rewards efficiency, quality, service, and dependability, a disengaged workforce diminishes the ability and capacity to deliver on these requirements. As serious as the consequences of the We–They Divide are, the benefits of crossing and closing the divide are that much greater. An engaged workforce not only contributes directly to an organization’s bottom line, but it also provides energy, commitment, and resilience in a world in which the potential for adversity is just around the corner. Ultimately, the We–They Divide is about relationships. It’s not about giving and taking and winning and losing; it’s about respecting and responding to basic human needs. Take the first step and discover how rewarding leading a WE culture can be personally, professionally, and organizationally.  I was spellbound. Here I was not reading a book about teams, but listening to the wisdom of a team who had lived it day in and day out. This experience occurred during a recent workshop on workplace safety. I had the privilege of working with a high-performing team that has a stellar safety record. The purpose of the workshop was to invite additional dialogue regarding a survey the team had taken. The plan was to seek additional detail and nuance about what they were thinking, feeling, and the experiences that influenced their ratings in this survey that measured areas of safety in their workplace ranging from corporate ethics to hazard recognition. While others took some time to warm to the task, this group was immediately engaged. They didn’t need encouragement or assurances of confidentiality. They jumped right in to a lively dialogue on each section. It wasn’t long before my curiosity was killing me—how was this group so invested, open, engaged, honest, and committed not just to safety, but to everything else they did? So I gently interrupted our conversation. “Can I deviate for a moment from the agenda and ask what drives your team and keeps all of you invested and committed to what you’re doing and how you do it?” Immediately, they started to share the glue that binds them together in their common pursuit of safety and performance. The first thing out of their mouths was a statement that indicated they each held a sense of common mission and purpose that drove their thinking, feelings and behavior. “We are very aware that what we do is very dangerous. One mistake has the potential to not only injure one of us—it could also have serious consequences for the people at this plant and the surrounding community. We don’t ever want that to happen.” What came next was, “We know each other and we care about each other.” And the caring extends to wives, children, girlfriends, and boyfriends. “We know a lot about each others’ families; we know their names, what schools they go to, the sports they play, and when things are going good and not so good. When you know people’s families, you have a deeper understanding that what we’re doing and how we’re doing it has far-reaching consequences. This also helps us to keep in touch with how a person is doing personally, and sometimes we pitch in to give a coworker a break when he or she needs it.” More Glue: We agree to disagree. “It’s taken us some time, but we’ve come to the conclusion that disagreeing is just part of life. We don’t get that upset anymore when we disagree. We give each other space and sooner rather than later we come around and work things out. We know that nothing is more important than safety and that keeps us from going off on each other.” We take personal accountability for our actions. “This has also taken us some time, but we’ve come to accept that we are the ones who can make a difference. It doesn't do us any good to complain, blame and look to somebody else to make our decisions. Our behavior and choices make the biggest difference, and we feel more secure and satisfied being accountable and in control.” This team had no formal training in teamwork; they had only learned from their experiences and continued to put what worked into practice. This created a culture in which purpose, accountability, respect, caring, and dialogue was the glue that kept them safe and performing to their individual and team best. They are what books are written about. That evening, I reflected again on the special opportunity I had to join in on these insightful and inspiring discussions. It became clear that what I teach and facilitate is what this group had intuitively and experientially put into practice. Their culture is infused with intrinsic motivation. They are motivated from the inside out. No one is dangling carrots or rewards or threatening them with consequences if they don’t act responsibly. They act safely and responsibly because it matters to them, and they take ownership and pride in it. Self-Determination Theory informs us that if people are given or find a sense of purpose in what they do; if they are given the resources, permission and support to have autonomy in making decisions; the encouragement and opportunity to develop relationships with each other and their managers; and the ability to influence the things that matter most to them—they will not only achieve, they will thrive. This team thrives in a very difficult environment. They do hard and dangerous work. Their success can be framed in a theoretical model, but what is most impressive is their commitment to make it stick—they are the glue. © Tom Wojick, The Renewal Group, September 2012 The speed and competitiveness of business in the 21st century requires your engines of productivity to be tuned and fueled. Workforce engagement continues to be a topic of debate within some organizations, while for others it has become an accepted and critical business metric. The Gallup Organization introduced the concept and brought attention to the potential impact that engagement can have on business results, but for many hard-nosed, analytical executives who are lacking the numbers or ROI, it remains one of those “soft and fuzzy” areas. A word of caution to the hard nosed; don’t try to merge onto the super highways of the 21st century with less than 50% of the power you need. In the 2010 Survey of Workforce Engagement by BlessingWhite, engagement levels around the world remained stable, which in my opinion is not a positive indicator because it means that 67% of the workforces of North American companies are disengaged. Think about that number for a moment! For me that translates into only a small minority of employees making the level of effort and contribution you need for your company to be competitive and successful! My friend and colleague, Carl Crothers made the following analogy in a recent workshop: “Imagine you have an 8, 6 or 4 cylinder automobile and you’re about to merge onto an interstate. You step on the accelerator expecting a burst of energy to get you safely into the flow of traffic, but the response you get is less than 50% of the power and energy you expected and needed.” This is an unfortunate reality for all types of organizations in North America; they’re running on less than 50% of the performance energy available because their individual human engines (Hearts and Minds) are disengaged. Talk about inefficiency, waste and lost opportunity. Hard nosed or not I think the picture is clear: if you’re not addressing workforce engagement you’re losing money and jeopardizing your competitiveness. Dan Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us wrote in a recent blog that the smallest unit of productivity is the individual. He questions how organizations will tap into that powerhouse, and goes on to say that “people are thirsting for context and purpose and as a leader one of the most powerful things you can do is provide that context.” This is the heart and art of engagement. Leadership is also addressed in the BlessingWhite survey. They emphasize that it is imperative that leaders align employee values, goals, and aspirations with those of the organization. It is through this alignment that organizations will achieve sustainable employee engagement, which will allow both to thrive: Engaged employees are not just committed. They are not just passionate or proud. They have a line-of-sight on their own future and on the organization’s mission and goals. They are enthused and in gear, using their talents and discretionary effort to make a difference in their employer’s quest for sustainable business success. In other words, don’t try to drive your business on the super highways of the 21st. century if your employees and organization are not operating on all cylinders! The report also highlights the following recommendations: * Measure less while acting more * Pay attention to culture * Managers are key leverage points in the engagement process In addition the report puts managers and CEO’s on notice that they must accept that they have a huge impact on developing and sustaining workforce engagement. Of course it’s a two way street; employees also have a responsibility for their engagement, but it won’t happen without leaders being actively engaged. Employees are looking for more than business competence, they want their leaders to be interpersonally and relationally competent. They want to trust in your abilities and character – and to understand your personal motivations. They want to see passion and commitment and most of all they want and need to have trust: trust that you will do the right thing. A word of advice to those who are still not convinced of the benefits of an engaged workforce, “More employees are looking for new opportunities than they were in 2008, suggesting that 2011 will be a challenging year for retention (and a hot market for firms looking to attract top talent).” This finding from the Employee Engagement Report is a like sign in your competitor’s windows, Talented Drivers Wanted. Do you want to take the chance of losing key employees you need to drive your business? If not, you might want to consider focusing on workforce engagement. One more word about engagement; it’s not about giving away the store. It’s not about more benefits, bonuses and rewards. It’s about tapping into and building intrinsic motivation – its there and waiting to be engaged. The Renewal Group’s Relationship – Centered Leadership® programs help managers and leaders discover, develop and deploy the interpersonal and organizational fuel to energize the engines of your future. As one recent participant said, “I now know what leadership is, what is required of me and that I want to be a leader.” |

Follow us

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed