Considering a Move to Management:

0 Comments

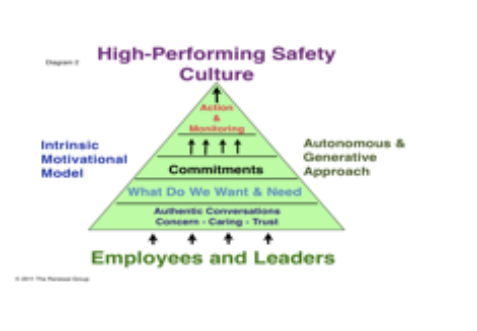

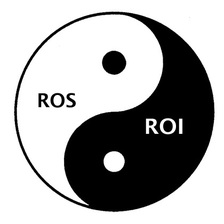

Normally, you assess an organization’s safety culture by observing how employees translate the company’s principles, values, attitudes, and goals into their behavior and decision-making. This seems like a pretty straightforward method, but beware of drawing conclusions based only on observations—you’ll fall into the assumptions trap. I’ve fallen into this myself by relying on direct observations and reports consisting of data based on observations, and I suspect I am not alone. The assumptions trap is a consequence of the way in which the human brain forms patterns to help us manage a complicated life more efficiently. Patterns feed our assumptions. They help us react, predict and make decisions regarding situations without having to assemble and sift through all of the details of what we are observing. The problem is the brain has no investment in making distinctions between fact and fiction. It takes in what it sees, dismisses what doesn’t fit, and draws a conclusion as expeditiously as possible. It will even add in data to fill any gaps just to complete the picture to fit the established pattern. This works very well when we need to slam on the brakes to avoid a child who darts into the road. However, this process has limits when used exclusively to assess or make assumptions about the effectiveness of a safety culture. David McLean, Chief Operating Officer for Maersk, expressed this realization in his article “The Importance Of Process Safety & Promoting A Culture of PSM.” “We were all very good at measuring personal safety performance, i.e. slips, trips, and falls, and this is very tangible, but did a good personal safety record mean we had a safe operation? Clearly not, as several major accidents had proven.” Avoid the Assumptions Trap by Engaging in Conversations “Can you hear me now?” was the key refrain from a Verizon commercial a few years ago. If you listen, you can hear employees using this same refrain in regard to their relationship with their managers. “They never listen to us, and when they do, they don’t hear what we are saying,” I’ve heard employees say. “They already have their minds made up.” Consider for a moment that managers spend 75% to 90% of their time in conversations! Who are they having these conversations with? And are they really listening or just filling in the gaps of existing beliefs and patterns? To understand and know one’s culture you must listen to it—not just to the words but also to the emotional texture of the words. A safety culture is created, nurtured and sustained by the breath and quality of the conversations that take place and the ones that don’t. “What people say and what they withhold matters,” said David Arella, founder and CEO of 4Spires. “Language trumps control. How the communication is initiated and conducted is often more important than what is communicated. An organization is a network of person-to-person work conversations during which information and energy is exchanged. Like cells in your body, the quality of these work-atoms determines the effectiveness of the whole. Attending to and influencing work conversations can help transform culture and improve collaboration.” The true nature of a culture is revealed through its conversations. If you want to understand your culture before making assumptions about your culture’s strengths and weaknesses—what motivates employees and what’s in their hearts and minds—you must engage in open and honest talk. Conversations can help give meaning to observations. Culture is made up of layers of conversations that are constantly vibrating and emitting information. Learning to notice and listen to these waves of information is a critical culture competency. It requires that leaders be committed to moving through the casual and superficial noise in order to gain insight into the organization’s authentic culture and discern what is really motivating employee performance. Don’t Use Data: How to assess your safety culture more effectively Edgar H. Schein, PhD, considered to be one of the foremost experts on organizational culture, believes that if you want to access your organization’s culture, bring together a group of employees who represent each part of the organization and provide an opportunity for them to dialogue about their issues, concerns, and the strengths and weaknesses they experience and perceive in the safety culture. Here is a simple but effective model to help organizations assess and transform their safety culture. It calls for leaders, managers, supervisors, and employees to engage in authentic conversations in which each can express and share their concerns and build the trust required to move forward. Leaders frequently expressed that they had reservations about engaging in these conversations, particularly those that reached below the surface. They preferred to use a survey (hard data). But after working with this model, not only did they obtain the data they wanted; they gained the commitment they needed from employees to work toward common goals. The following questions can help assess if your have a culture that values conversations or if it is reliant on assumptions and patterns. · Is it like pulling teeth to get employees to talk in meetings? · How often do safety leaders practice walking and talking about the site? · Is the word stupid—or a similar insult—ever used to describe safety incidents or the employee involved? · What emotion(s) best describes the mood of the safety culture? Frustration, boredom, disappointment—or excitement, curiosity, and passion? · Do managers abhor meetings and feel that they are a waste of time? · How often have employee safety recommendations been implemented? This self-assessment will begin to give you an indication if the conditions of your safety culture are conducive to meaningful dialogue; if it encourages open and honest conversations or stifles it. A word of caution though: Just because employees may be reluctant to engage in conversations doesn’t mean they don’t want to be heard. Their behavior may be more about their lack of trust, fear of blame, or a result of previous conversations that resulted in a negative experience. A positive safety culture is a repeatedly observant one, not just of behavior but also of its tone and content. Safety leaders would be well served to develop a practice of deeply listening and observing before making assessments and judgments. Contact Tom Wojick for more information on how to introduce conversations into your culture 401-525-0309 [email protected]  A familiar and popular business performance metric is ROI—Return on Investment. For many, this is the keystone of workplace culture, driving business strategy and decisions as well as the behavior of managers and employees. Most businesses won’t invest capital or other resources unless there is a direct positive financial gain from the investment. It’s a no brainer—if a business wants to be successful and remain viable, it must generate a return. But is there a dark side to ROI? Balancing ROI and ROS There is a performance metric that is as critical to organizational success as ROI: ROS—Return on Safety. Providing a healthy balance to ROI, ROS (#returnonsafety) is a metric that applies to every business, though it carries particular significance in manufacturing and production industries such as oil and gas, transportation, chemical, farming, and recycling. In these workplaces, humans interact closely with heavy machinery and hazardous substances, and it is not an unproven theory that focusing too intently on ROI can affect employee safety and decisions as well as organizational success. In the last five years we’ve witnessed tragedies that serve as prime examples of what happens when organizations’ focus on ROI is dominant: Upper Big Branch Mine (29 miners killed): A final report on the West Virginia tragedy indicated that Massey Energy had a culture of willful disregard for safety in favor of optimized profit and production. Deepwater Horizon drilling platform explosion (11 workers killed): A statement from the final report noted that “the culture of safety is less strong than the imperative to meet deadlines, what has been referred to in the Deepwater Report by the Center for Catastrophic Risk Management as an ‘imbalance between production and protection’” (Forbes.com, 11/28/2012). General Motors’ faulty ignition switch (31 deaths): Began with an ignition switch that was found to be defective in 2001. GM’s CEO, Mary Barra, stated to a congressional committee investigating the failure, "The customer and their safety are at the center of everything we do." Yet, GM’s own internal investigation, The Volukas Report, noted that there were conflicting messages regarding ROI and safety: “Two clear messages were consistently emphasized from the top: 1) ‘When safety is at issue, cost is irrelevant’ and 2) ‘Cost is everything.’” One engineer said that the emphasis on cost control at GM “permeates the fabric of the whole culture.” The Price of Imbalance The cost of these disasters combined is estimated to top 50 billion dollars. But the real tragedy is that as many as 71 people lost their lives because employee safety became an afterthought, or was never a priority to begin with. This is the dark side of ROI. Could a culture that focuses on ROS, instead, have prevented these disasters? Most experts and authorities say yes. Peter Kelly-Detwiler’s 2012 Forbes article, “BP Deepwater Horizon Arraignment: A Culture That ‘Forgot to be Afraid,’” addresses not just the Deepwater Horizon disaster but others as well: “The gist of all of these inquiries and reports is pretty much the same: repetition, complacency, complicated technology, and a poor culture of safety combined with the production/protection imbalance is a recipe for failure. This can generally be remedied by the appropriate focus on best available safety practices and technology.” Calculating the Worth of ROS ROS as a metric is not as easy to calculate as ROI. It doesn’t show up in quarterly profit and loss statements and if it does its typically as an expense, therefore organizations have difficulty assessing its value to the bottom line—something many CEOs, under pressure from shareholders and the financial markets, can’t see beyond. Instead, ROS requires leaders to have a vision that extends beyond quarterly reports. These men and women must have a steadfast commitment to safety, the courage to confront the short-term thinking of Wall Street, and a willingness to reject the idea that production and profit achieved at the expense of employee safety is a sustainable business strategy. Leaders who respect the value proposition of ROS understand how intimately safety is related to quality, reputation, efficiency, innovation, and worker engagement and loyalty. How One Company Benefitted Paul O’Neill, CEO of Alcoa from 1987-2000, was a leader who understood ROS and had the foresight to make it his keystone business philosophy and strategy. In “How Changing One Habit Helped Quintuple Alcoa’s Income,” Drake Baer writes: “The emphasis on safety made an impact. Over O'Neill's tenure, Alcoa dropped from 1.86 lost work days to injury per 100 workers to 0.2. By 2012, the rate had fallen to 0.125. “Surprisingly, that impact extended beyond worker health. One year after O'Neill's speech, the company's profits hit a record high. “Focusing on that one critical metric, or what (writer Charles) Duhigg refers to as a ‘keystone habit,’ created a change that rippled through the whole culture. Duhigg says the focus on worker safety led to an examination of an inefficient manufacturing process—one that made for suboptimal aluminum and danger for workers. “By changing the safety habits, O'Neill improved several processes in the organization. When he retired, 13 years later, Alcoa's annual net income was five times higher than when he started.” An ROS mindset instills organizational leaders with the compassion, courage, and values of a Paul O’Neill. To assess the balance and tension between ROI and ROS in your business, review the following list. 10 warning signs your culture is ROI-influenced: 1) The person who is responsible for safety does not report directly to the CEO 2) The CEO and managers rarely discuss safety at strategy, HR, production, quality, and sales and marketing meetings. 3) The company’s safety vision is not linked to the business strategy or worst it is non-existent. 4) Managers throughout the organization fail to consistently emphasize safety or are resistant to safety initiatives. 5) The organization has few if any feedback loops for continuous safety improvement. 6) Metrics used to evaluate individual and team performance have minimal to no weight placed on safety. 7) Employees are not familiar or are skeptical of the sincerity regarding the company’s safety vision and values. 8) Training and development do not emphasize safety. 9) New employees and contractors are not first and formally introduced and oriented to the organizations safety vision and values. 10) Employees are fearful of negative repercussions for reporting safety incidents, risks, and hazards. This is just the beginning though. Truly understanding what drives your business requires a more nuanced and careful approach than checking some boxes. I’ve seen many situations in which the person responsible for EHS reported directly to the CEO yet felt disrespected and undervalued, and vice versa. Assessing the motives of any organization requires a hard look at these relationships. Ultimately, an organization that creates a culture more heavily influenced by ROI than safety cannot ensure success for its shareholders or stakeholders. Choosing to gamble the health and wellbeing of employees for production and profit, these businesses will always be a risky—not reputable or ethical—investment. ROS-Return on Safety C The Renewal Group 2015 References and Acknowledgements: Volukas Report: http://www.autonews.com/article/20140605/OEM11/140609893/read-gms-internal-report-from-investigator-anton-valukas-here I want to acknowledge Hugo Moreno’s article, “10 Warning Signs of a Weak Culture of Quality” (Forbes Insight), which provided the basis for the checklist used in this article  One thing you can count on is life being a mix of good times, bad times, joy, and sorrow. None of us can predict what tomorrow will bring. Consider the tragedies our nation, communities, and families have experienced in the past years: 9/11; Katrina; Sandy Hook. The people affected by these unexpected events didn’t plan for the pain and sorrow they would experience, and yet they had to find a way to make it through the day and each day thereafter. What is it that gets us through tragedies and everyday adversities? It’s not the size of our bank accounts, or our jobs, or our possessions; it’s an entirely different resource more valuable than money, available to all of us, all of the time. It is resiliency. Resiliency springs from our innate desire for life. It helps us persist through the bad times until we regain our footing and are once again productive, positive, and hopeful. Although we all possess resiliency, the strength of our resilience only grows as much as we nurture it—by making daily deposits. Think of a savings account. Every day life presents us with small and large challenges, all of which withdraw resiliency from our account. If we don’t, in return, make deposits, we might find ourselves lacking the resiliency needed to keep our spark for life bright. Here are a few ways, or daily deposits, you can make to your resiliency account. When you encounter an unexpected adversity, you’ll be grateful to know your account is full. Just say no to the negative voices: There is a part of your brain that acts as a safety alert system designed to warn you of suspected danger. It also reminds you of past negative experiences, hoping to make sure you avoid similar experiences moving forward. Sometimes, though, this makes us feel incapable of learning from the situation and trying again with confidence. Though your brain thinks it’s doing you a service—trying to keep you from feeling pain again—know when to say “no” to negative talk. Simply say, “Thanks for your concern, but I’m not going to listen to you for a while. I’ve got important work to do.” Give yourself the room and permission you need for your positive voice, because it wants to help you heal. “This is a rough period I’m going through,” you might say, “but I know I’ll make it. I’ll be stronger.” Build your circle of fans: And I don’t mean through social media. You need to build a close circle of friends that are honest, vulnerable, and helpful, and that participates in an equal give and take (of time, opinions, ideas, and so on). Nothing takes the place of face-to-face contact, either. Make sure you add at least one of the following to your circle: · Someone with whom you feel comfortable sharing your most honest thoughts and feelings. · Someone who will give you a good kick in the behind if they see you’re not taking the action needed to get to where you want to go. · Someone who will listen and offer his or her honest perspective. Push and be compassionate: Moving through difficult times is never easy, and it is natural to want to retreat and avoid anything you think will be difficult, burdensome, or over stimulating. But resiliency doesn’t mean retreat. Whatever might be weighing you down, whatever roadblocks you see before you--push. Keep moving. Get thoughtful, creative, and simplistic in your approach. Take small steps, start over, or try another route. Whether or not you meet your end goal, you will have added a dose of resiliency to your account. Most importantly, use this time to practice patience and compassion with yourself. You are as deserving of your own understanding and acceptance as anyone else. Practice your smile: In times of adversity or sorrow, it’s easy to be overcome with pain and doubt, and to let these thoughts tinge our view of the world. When you can, find things worth smiling about: a cute kitten, a joyful child, a funny comedy clip on television. Make it a point to point out what’s nice in life, even if it’s one small thing every day. These small positive moments ultimately lead to positive changes in our thoughts and feelings. When smiling feels the hardest, that’s when you need it the most. That’s when your deposits will be the largest, though they may seem small. Emotions and Culture – Drivers of Human Behavior " I can't say I'm sorry enough. I'm sure I'll be criticized, but it's true. I felt awful. It wasn't my intention. […] It's not what I wanted to see or anyone to see." These are the words of Shawn Thornton, a professional hockey player for the Boston Bruins, after attacking and injuring an opponent during a recent game. Suspended by the National Hockey League as punishment for his behavior, the consequences of Thornton’s actions affect him and his team. Why did Thornton attack his opponent in the first place? Based on his response—“It wasn’t my intention”—I suspect he allowed his emotions to take over. In other words, he was “emotionally hijacked.” We’ve all had experiences of being emotionally hijacked, when strong emotions suddenly wield control of our behavior. Our response after the episode is usually the same as his, too: “I don’t know why I acted that way.” Intense emotions can dominate our thinking and drive our actions—they are powerful sources of energy. In emergency or crisis situations, they work to keep us out of harm’s way: Fight, freeze, or flee. But in other, less noble situations, they cause us to react in ways we later regret (“I felt awful”). Having the emotional awareness and insight to prevent or short circuit the hijacking process brought on by intense emotions is called emotional intelligence, a necessity in a world filled with situations that can easily give rise to intense emotions. Carefully handling strong emotions, rather than quickly giving into them, is critical in making reasoned decisions that work for us rather than against us. I also believe an even more powerful force than emotions was involved in Thornton’s reaction that night, a force that oftentimes makes it difficult for individuals to navigate situations that ignite intense emotions: culture. Suppose you are in a business meeting when a colleague pokes fun at your presentation. His comments are humorous but rude and uncaring. You might notice your muscles tensing and your mind racing. Will you walk over and throw your morning coffee in his face (fight)? Excuse yourself and leave the room (flee)? Or stand motionless, unable to respond (freeze)? Since most office business cultures do not encourage, support, or condone physical attacks, you opt not to throw your coffee. What you decide to do instead is respond in an emotionally intelligent way: “Your comments leave me feeling put down and I’m not sure how they have contributed to helping us find a solution. In the future, it would be helpful for me if you could be more specific and constructive with you comments and feedback.” Thornton’s attack took place in a business environment, or culture—professional hockey—that encourages, condones, and supports fighting as a means of solving disputes. For many years, hockey teams employed players for their fighting skills rather than their athletic abilities, according to Seth Wickersham in his article “Fighting the Goon Fight.” It was the role of these enforcers to protect their team’s star players from opponent harassment while also goading the opponent’s star players into a fight. Ben Livingston, a sports journalist, supports this theory in his article “The Bizarre Culture of Hockey.” “The only constant in fighting is that you are assessed a penalty for doing it,” he writes. “There exists a bizarre practice of allowing fighting to occur, while at the same time penalizing the participants for doing it. This has lead to it being called a ‘semi-legal’ practice.” Another potent factor in becoming emotionally hijacked - The emotions of others. In Thornton’s case, this meant the taunting and yelling stirred up by his fans. When a fight breaks out in hockey, fans cheer furiously for someone to be physically punished. Many, in fact, are drawn to the sport for its violence. Though Thornton was penalized for his part in the incident, his co-conspirators—the fans and the culture of professional hockey—escaped without penalty. As in any emotionally intense situation, Thornton’s behavior was the tip of the iceberg. It is the stronger influences and motivators—those that support and permit transgressions like his—that remain below the surface, where the culture of hockey exists. Rules and regulations are never a primary factor in human behavior unless they are in full alignment with a culture’s mission, values and strategic objectives. Rules merely provide cover for an organization so they can identify and blame transgressors and escape accountability and culpability. We’ve seen this with the likes of Enron, British Petroleum (BP), Massey Mines and most recently, the world’s major banks. All professed to be motivated by high ethical standards and comprehensive safety rules and regulations, but the cultures that have dominated these businesses runs contrary to their hollow words. It is emotions and culture that have the greatest effect on human behavior and any organization that attempts to influence and enforce positive behavior with regulations alone will remain vulnerable to disruption, loss, and plenty of emotional hijacking. Thornton said, ”I can’t say I’m sorry enough,” but the burden and responsibility of his actions do not sit entirely on his shoulders. It’s difficult for any employee to make the “right” choices when organizational rules give direction but the culture of the organization is ambiguous about enforcement and in some cases turns a blind eye to negative or unsafe behavior because it supports the organization’s explicit desire for profit, production, entertainment, and risk taking. The NHL, in which fisticuffs remain an integral part of the sport’s culture, penalizes individuals for fighting, but the behavior of its players remains unchanged, because below the surface enforcers are rewarded and celebrated for their transgressions by fans, teammates, and the media. Banks will not change their culture of risk taking for profits when CEO’s get bonuses and salary increments after being penalized billions of dollars for violating regulations. And safety will always be secondary when employees are pushed to keep production up at all costs. The unfortunate aspect of these “Trojan Horse Cultures” is that they present and say one thing, but inside, where true culture resides, are the drivers of behavior, which often put their employees at the lower rungs of the organization in harms way as they attempt to navigate between the rules and what the culture is condoning and endorsing. I’ve worked for the past ten years assisting organizations in identifying where there is culture misalignment and working with them to restore and or build cultures that authentically and consistently align with their mission, values and strategic objectives. The work is hard, but the rewards are significant and produce results that are sustainable and profitable. Most importantly, they become organizations in which leaders and employees feel pride, take ownership and work jointly to insure success, and where leaders and employees feel accountable and safe in stating. “I can’t say I’m sorry enough.”  Which side of the divide are you on - are you a We or They? The they’s and we’s have been at odds before the Hatfields and McCoys starting shooting at each other. The We–They Divide is not unique or new. It has existed since the dawn of employee-manager relationships and to this day it continues to infect, constrain, and confound organizations and leaders. The impact of the We–They Divide on an organization is similar to any infection: Inevitably, it takes a toll on everyone. It diminishes work efficiency, quality, and organizational resilience, and can be the difference between success and failure.

The divide is not just an employee satisfaction or morale issue, though; it strikes at an organization’s bottom line. Towers Perrin’s 2008 Global Workforce study found that We–They Divides have negative consequences on operating margins, but, conversely, if a divide is reduced it can improve an organization’s bottom line. With all the financial, quality, performance, safety, and competitive risks this kind of divide exposes an organization to, and with all the research that validates its existence, why do organizational leaders continue to underestimate its impact? For many, the We–They Divide is untraveled territory with few or trusted maps available to assist them in navigating their way. Traditional organizational constraints like limited financial resources are issues most leaders feel equipped to handle. They can close gaps by reducing or cutting expenses, look for additional financing, or increase revenue by reaching more customers or raising prices. When it comes to the We–They Divide, the solutions are less formulaic. Feeling less confident, lacking in experience, and without training in how to recognize and approach the issue, many leaders are slow to address divides in their workplace. One manager explained to me, “We have only one chance to get this right, therefore we need to go slow.” While slow approaches usually indicate thoughtfulness and precision, in this case it indicates a lack of experience, confidence, and trust. The manager’s adherence to a slow approach only increases the chances that his workplace’s infection of disconnection will spread and widen the divide, making treatment that much more difficult. Employees are more concerned about serious commitments to address the We – They Divide than they are of mistakes. What Is the We–They Divide and the Reality of Perception The Conference Board, a global, independent business membership and research organization working in the public interest since 1916, developed a definition for a concept called employee engagement, which describes the degree of emotional and intellectual connection or disconnection an employee has for his/her job, organization, manager, and coworkers that, in turn, influences and motivates him/her to give and apply additional discretionary effort to his/her work. The We–They Divide is the emotional and intellectual distance between leaders and employees—it is the degree of disconnect. Human behavior is based on perception. Therefore, whether correct or incorrect, fair or unfair, perceptions are each person’s (group’s) reality, and it is these perceptions that create the divide: We Perceptions vs. They Perceptions. Our perceptions create a set of default assumptions that remain the undercurrent of our thoughts and feelings regarding any given topic. A common perception I hear from employees concerns the “invisibility of leaders.” It sounds like this: “We never see him. The only time he leaves his office is when something negative happens. Then he’s in our face wanting answers.” It’s not difficult to predict the assumptions that could arise from this type of perception. While some employees might assume their leader doesn’t care about them, others might assume you only receive attention when you do something wrong. The worst? Some might believe their leader thinks he or she is too good to associate with them. Sadly, most leaders are taken aback to hear of their employees’ assumptions. “I never knew.” While some immediately commit to change, others start explaining, defending, and offering examples of employee engagement. The space between these two perceptions is another example of the We–They Divide. Though some believe they cannot control what others think and assume, and that “no matter what is done employees will always find something else to complain about,” we know this not to be the case. There are a number of methods and approaches that leaders and organizations can take to reduce divide. There are six We -They Divide Prevention Measures leaders can take to positively influence employee perceptions and assumptions that will prevent the divide from widening—and even begin to reduce it. However, it does takes a much more comprehensive initiative to transform a We–They Culture in which employee disengagement is a serious impediment and threat to an organization’s optimal performance to a We Culture. For insight how a client organization accomplished this read, Leaders Don't Motivate - They Create The Conditions For Self-Motivation on this site. The following are We–They Divide Prevention Measures taught by Nicole Gravina, Ph.D. When leaders integrate and apply these concepts while making decisions, communicating with employees, designing systems/processes, and working with each other, they can minimize the perception of the divide and increase cooperation and commitment from employees. Proximity: Employees take particular notice if leaders are in close proximity or if they are distant, and the perception of distance increases the divide. Therefore, a lack of physical, social, and emotional presence by a leader contributes to negative perceptions and assumptions in the We–They Divide. Communicating primarily by email, not attending or holding employee meetings and the absence of informal social contact in meetings, and being absent at informal and formal social events can all contribute to the perception that a leader doesn’t like us, care about us, or understand us. Leaders must be proactive in their efforts to finding ways to bring themselves into closer proximity with their employees. If your office is distant from the people you manage, schedule time on a regular basis to leave your office and meaningfully interact with your employees in their space. Take time to learn about their social and family situations. Engage on a social level. Similarity: is to work against the common perception that leaders are better and more privileged than their hourly workforce. Employees understand that leaders are paid differently and have additional benefits, but they don’t like when their leaders present themselves as better, smarter, wiser, or more privileged. The more you can emphasize your common human similarities, the closer a connection (emotional proximity) will be between a leader and his/her employees. Though you may be fortunate enough to rise on the corporate ladder, never lose sight of where you came from and the people who helped you climb that ladder along the way. Much to their disadvantage, leaders operate in bubbles and cast long shadows. Seldom do they receive unvarnished feedback, which they need in order to understand employee perceptions and behavior. To be an effective leader, one must create opportunities and structural mechanisms that allow for unfiltered feedback. Inconsistent Application of Rules and Policies: Nothing is more irritating to employees—or sends the “I’m better” message—than when leaders excuse themselves from basic workplace policies. Management should always demonstrate its similarity and commitment by adhering to its own rules. Opposing Goals: Are the goals established in various areas of the organization interdependent or independent of the organization’s overarching mission? I have seen incentive structures for a sales groups conflict with the corporate responsibility and quality departments, and instances when safety procedures and goals in a manufacturing organization are not followed because they would have interrupted production goals. Is your team aligned? Differences in Availability of Resources, Time, Feedback, and Recognition: Everyone notices if someone else gets more than they do. If you had brothers or sisters, you know what I mean. Leaders need to be attentive to this aspect of human nature. If an employee or a group of employees perceives that someone is getting more than they are, not only will they think this it unfair, they’ll also feel less important. I’m not simply referring to hard resources like money and equipment, but the softer and less tangible resources such as demonstrations of appreciation and recognition. Though many leaders don’t value recognition as a resource, employees do. Leaders who understand and develop a practice of appreciation and recognition are providing employees with emotional and psychological resources that will motivate and strengthen their commitment for years to come. Lack of Information and Follow-Through: Assuming people know and understand your intentions and your purpose, and that of the organization, is a mistake. Communicate, communicate, and communicate more. Leaders must set a goal to actively communicate and solicit feedback from employees and not stop until you hear, “You’re killing us with all this communication!” Once you hear this statement, you’ll know you’re on the right track. Follow-through is the period at the end of a sentence. One of the downfalls of employee suggestion programs is that employees seldom get feedback or follow-through on the status of their suggestion. Employees will hang onto an issue until they feel the loop has been closed, leaders must follow through, which in turn builds trust. A colleague of mine, Richard Hews, instructs managers on the “Cycle of Commitment or Promise. One of the essential aspects or steps in the cycle is the declared satisfaction. It is here where the initiator and the performer declare their satisfaction if the request was completed to the requirements. Punishment-Oriented Culture: Nothing is more destructive than a culture in which a hammer is the primary leadership tool and every employee feels like a nail. It is divisive, creates aggression, and kills engagement. No high-performance culture is built on a foundation of punishment. This type of culture only exacerbates the We–They Divide, turning it into a chasm. Summary The We–They Divide is a silent and serious threat that can strike the bottom line of an organization and jeopardize its stability and competitiveness. Disaffected and disengaged employees lack the commitment, creativity, and energy to give their discretionary effort. And in a continuously changing and challenging global marketplace that rewards efficiency, quality, service, and dependability, a disengaged workforce diminishes the ability and capacity to deliver on these requirements. As serious as the consequences of the We–They Divide are, the benefits of crossing and closing the divide are that much greater. An engaged workforce not only contributes directly to an organization’s bottom line, but it also provides energy, commitment, and resilience in a world in which the potential for adversity is just around the corner. Ultimately, the We–They Divide is about relationships. It’s not about giving and taking and winning and losing; it’s about respecting and responding to basic human needs. Take the first step and discover how rewarding leading a WE culture can be personally, professionally, and organizationally. |

Follow us

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed