I was perusing possible gifts for my grand-kids this past Christmas when I read this line on the cover jacket of the book Spirits Princess and thought about how exciting and entertaining this book might be. What really captured my attention was the phrase “one breath away from catastrophe.”

How many times in our lives have these words been meaningful? I can recall a few near-catastrophes in which I was literally one breath away from a serious accident. I remember sitting in my car after losing control on the first icy road of my driving career; I was one breath away from going down an embankment. I recall one summer backing up a dump truck loaded with gravel to fill in around the foundation of a home. There was a small rise of dirt, and every time I tried to slowly back up the rear tires would spin. After I pulled forward and gave it a little more gas, I found myself and the truck within a breath of tipping over into the foundation. I couldn’t dump the load or the truck would have flipped. Holding my breath, I slowly got out of the cab and embarrassingly enlisted a guy with a bulldozer who was working in the next lot to help rescue my truck and safe my summer job.

I also vividly and sadly remember sitting with both my Mom and Dad when they took their last breaths. Unfortunately, the full meaning of this word escapes our attention until we are present in these moments and realize that it is the essence of life and death.

I wonder how many times our accidents and injuries and catastrophes were literally one breath away form a different result? I suspect many more than we realize. Isn’t a near-miss really just a “one breath away” moment?

The Chaotic and Hectic World of Work

Todays’ work environments are filled with increased and competing demands and technological advancements and distractions. Multi-tasking has become a way of managing this new reality. Some say this new pace of work leaves them breathless.

In a recent meeting with a group of managers and supervisors, we explored the question, “Are there current conditions in our culture that might be creating the potential for safety issues?” Some concerns surfaced immediately: “We are in a state of chaos!” “Everybody has an agenda and thinks it’s the priority.” “We are driving our operators to distraction and increasing everyone’s stress levels.” “If this continues, it’s not if we will have an accident, it’s when and how serious.”

What if “one breath away” was not an expression of a close call, but a method or practice that could reduce chaos and prevent a near-miss from becoming an unfortunate reality?

The human factors that most frequently contribute to or are the primary reasons for accidents and injuries are complacency, stress, fatigue, distraction, and haste. Each of these has many root causes that would need to be be fully addressed. However, there is a scientifically proven intervention that can provide temporary improvement or relief from the effects of these factors and can prevent that critical moment form turning bad.

Complacency, stress, fatigue, distraction, and haste create the conditions for accidents because they steal one’s attention and focus away from the task at hand. To prevent this, we employ a simple, inexpensive, and effective tool that can bring one’s connection, respect, attention, and focus back to work.

The Power of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is an ancient practice the uses the breath to bring one’s full attention and awareness to the present moment.

The purpose of mindfulness is to create moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and surrounding environment. Over the last 10 years, mindfulness has entered American mainstream and business culture. Numerous companies offer mindfulness training to their employees as a benefit and as a tool for improving performance. One notable company, Google, offers its employees a course on mindfulness that is 50 hours long. It is the highest rated course in the history of Google.

The essence of mindfulness is breath, called mindful breathing. Research has shown that even one six-second mindful breath is effective at calming the body and mind and improving focus. This breathing tends to be slow and deep, which stimulates the vagus nerve, activating the parasympathetic nervous system. This system regulates our heart rate and blood pressure, which when lowered helps to produce calmness, increases awareness, and lowers stress. This moment of mindfulness can also help to temporarily offset the symptoms of fatigue.

The skill of mindful breathing is used by the worlds best athletes in all sports. Watch any world class golfer, tennis player, skier, track athlete, or baseball player, especially when hitting—they all employ mindful breathing to calm themselves and to better focus at the task at hand. If it works for professional athletes, shouldn’t it also help our workforce athletes improve their performance?

Choose Mindfulness over Mindlessness

Technology is revolutionizing workplace safety. From robotics that keep humans out of harm’s way, to man-down systems that send out alerts for employees in need of assistance, our workplaces are safer than ever. But there is still one area that is persistently and intimately connected to accidents and injuries that technology has not fully solved: the human factor.

The contribution of human carelessness or mindlessness to all accidents and injuries ranges from 50% to 90%. The ability to reduce the involvement of human factors can have a significant affect on an organization’s Return on Safety.

Although technology is rapidly creating solutions to safety issues, our hectic pace continues to thrive, increasing the chances that human errors will continue to significantly contribute to accidents, injuries, and near-misses. Organizations can fight this by creating the conditions for a mindful workplace.

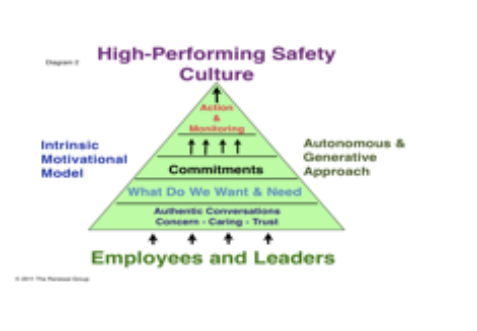

To create a mindful work environment in which employees feel motivated, comfortable, and encouraged to practice mindfulness requires management’s active involvement in setting expectations and creating new norms that might be contrary to the existing organizational culture. Management must be active role models – they must be believers.

Getting Started:

How to create a mindful work environment

Implement it mindfully. This is not a program. Mindfulness is a respectful approach to work and life.

Take the time to educate leaders and managers on the history, science, and research behind mindfulness, how it works, and why it contributes to improved human performance. Invite an expert on organizational mindfulness to conduct a training session to assist with the process and to demonstrate mindful breathing.

Institute a moment (six seconds) of mindful breathing before and at the conclusion of all management meetings for one month. Take notice if the climate of the meetings changes. Ask managers if they notice a difference

Once managers become comfortable and notice the affect it has on the tone and results of the meetings, ask managers to introduce the same practice in their meetings. First, have them explain the Why, have them share their experiences and invite their employees to participate for one month. Ask for feedback after that time.

Remember, this is just a six-second breath before and after meetings and when starting and stopping a task. This not mediation—it is one mindful breath that signifies one’s respect for their work and themselves, which will create a safer and healthier organization.

Before long, mindful breathing will become a standard operating procedure (SOP), not because it is mandated, but rather because all employee will notice the benefits and improvements it brings to their work and life. A mindful breath won’t change the hectic and demanding world we live and work in, but it will reduce our mindless approach to the task at hand and it just may be the breath that prevents an accident or injury.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed