Considering a Move to Management:

0 Comments

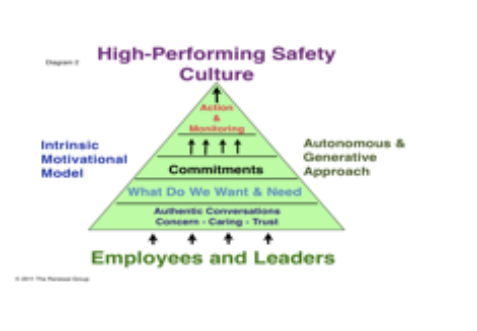

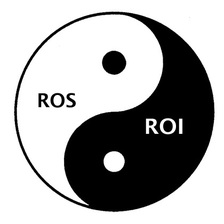

“He was a boy who loved to hear tales where the hero’s life was always one breath away from catastrophe.” I was perusing possible gifts for my grand-kids this past Christmas when I read this line on the cover jacket of the book Spirits Princess and thought about how exciting and entertaining this book might be. What really captured my attention was the phrase “one breath away from catastrophe.” How many times in our lives have these words been meaningful? I can recall a few near-catastrophes in which I was literally one breath away from a serious accident. I remember sitting in my car after losing control on the first icy road of my driving career; I was one breath away from going down an embankment. I recall one summer backing up a dump truck loaded with gravel to fill in around the foundation of a home. There was a small rise of dirt, and every time I tried to slowly back up the rear tires would spin. After I pulled forward and gave it a little more gas, I found myself and the truck within a breath of tipping over into the foundation. I couldn’t dump the load or the truck would have flipped. Holding my breath, I slowly got out of the cab and embarrassingly enlisted a guy with a bulldozer who was working in the next lot to help rescue my truck and safe my summer job. I also vividly and sadly remember sitting with both my Mom and Dad when they took their last breaths. Unfortunately, the full meaning of this word escapes our attention until we are present in these moments and realize that it is the essence of life and death. I wonder how many times our accidents and injuries and catastrophes were literally one breath away form a different result? I suspect many more than we realize. Isn’t a near-miss really just a “one breath away” moment? The Chaotic and Hectic World of Work Todays’ work environments are filled with increased and competing demands and technological advancements and distractions. Multi-tasking has become a way of managing this new reality. Some say this new pace of work leaves them breathless. In a recent meeting with a group of managers and supervisors, we explored the question, “Are there current conditions in our culture that might be creating the potential for safety issues?” Some concerns surfaced immediately: “We are in a state of chaos!” “Everybody has an agenda and thinks it’s the priority.” “We are driving our operators to distraction and increasing everyone’s stress levels.” “If this continues, it’s not if we will have an accident, it’s when and how serious.” What if “one breath away” was not an expression of a close call, but a method or practice that could reduce chaos and prevent a near-miss from becoming an unfortunate reality? The human factors that most frequently contribute to or are the primary reasons for accidents and injuries are complacency, stress, fatigue, distraction, and haste. Each of these has many root causes that would need to be be fully addressed. However, there is a scientifically proven intervention that can provide temporary improvement or relief from the effects of these factors and can prevent that critical moment form turning bad. Complacency, stress, fatigue, distraction, and haste create the conditions for accidents because they steal one’s attention and focus away from the task at hand. To prevent this, we employ a simple, inexpensive, and effective tool that can bring one’s connection, respect, attention, and focus back to work. The Power of Mindfulness Mindfulness is an ancient practice the uses the breath to bring one’s full attention and awareness to the present moment. The purpose of mindfulness is to create moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and surrounding environment. Over the last 10 years, mindfulness has entered American mainstream and business culture. Numerous companies offer mindfulness training to their employees as a benefit and as a tool for improving performance. One notable company, Google, offers its employees a course on mindfulness that is 50 hours long. It is the highest rated course in the history of Google. The essence of mindfulness is breath, called mindful breathing. Research has shown that even one six-second mindful breath is effective at calming the body and mind and improving focus. This breathing tends to be slow and deep, which stimulates the vagus nerve, activating the parasympathetic nervous system. This system regulates our heart rate and blood pressure, which when lowered helps to produce calmness, increases awareness, and lowers stress. This moment of mindfulness can also help to temporarily offset the symptoms of fatigue. The skill of mindful breathing is used by the worlds best athletes in all sports. Watch any world class golfer, tennis player, skier, track athlete, or baseball player, especially when hitting—they all employ mindful breathing to calm themselves and to better focus at the task at hand. If it works for professional athletes, shouldn’t it also help our workforce athletes improve their performance? Choose Mindfulness over Mindlessness Technology is revolutionizing workplace safety. From robotics that keep humans out of harm’s way, to man-down systems that send out alerts for employees in need of assistance, our workplaces are safer than ever. But there is still one area that is persistently and intimately connected to accidents and injuries that technology has not fully solved: the human factor. The contribution of human carelessness or mindlessness to all accidents and injuries ranges from 50% to 90%. The ability to reduce the involvement of human factors can have a significant affect on an organization’s Return on Safety. Although technology is rapidly creating solutions to safety issues, our hectic pace continues to thrive, increasing the chances that human errors will continue to significantly contribute to accidents, injuries, and near-misses. Organizations can fight this by creating the conditions for a mindful workplace. To create a mindful work environment in which employees feel motivated, comfortable, and encouraged to practice mindfulness requires management’s active involvement in setting expectations and creating new norms that might be contrary to the existing organizational culture. Management must be active role models – they must be believers. Getting Started: How to create a mindful work environment Implement it mindfully. This is not a program. Mindfulness is a respectful approach to work and life. Take the time to educate leaders and managers on the history, science, and research behind mindfulness, how it works, and why it contributes to improved human performance. Invite an expert on organizational mindfulness to conduct a training session to assist with the process and to demonstrate mindful breathing. Institute a moment (six seconds) of mindful breathing before and at the conclusion of all management meetings for one month. Take notice if the climate of the meetings changes. Ask managers if they notice a difference Once managers become comfortable and notice the affect it has on the tone and results of the meetings, ask managers to introduce the same practice in their meetings. First, have them explain the Why, have them share their experiences and invite their employees to participate for one month. Ask for feedback after that time. Remember, this is just a six-second breath before and after meetings and when starting and stopping a task. This not mediation—it is one mindful breath that signifies one’s respect for their work and themselves, which will create a safer and healthier organization. Before long, mindful breathing will become a standard operating procedure (SOP), not because it is mandated, but rather because all employee will notice the benefits and improvements it brings to their work and life. A mindful breath won’t change the hectic and demanding world we live and work in, but it will reduce our mindless approach to the task at hand and it just may be the breath that prevents an accident or injury.  “Without imperfection, neither you nor I would exist.” ~ Stephen Hawking The politicians, pundits and journalists who are against the Iran Nuclear Agreement focus on one point: it’s not perfect and could be better. Most of us know from experience that humans are not perfect. Isn’t it unrealistic to expect that any agreement created by imperfect beings be perfect? We are not in a position to force capitulation. Negotiation is a process that creates a path forward in which each party retains its dignity, propelled by the desire to give up something of personal value in order to gain something of greater value for everyone. Agreements are never perfect. If Congress thwarts this agreement, what are the alternatives? We could continue and even increase sanctions, but our allies will not stand by our side, and if we are the only country applying sanctions the effects will be minimal—not a perfect alternative. Fifty years of embargoing and sanctioning Cuba has shown us that these alternatives can and will cause increased defiance. We imposed strict sanctions on Russia, yet Putin doesn’t seem a bit inclined to return Crimea. We could also go to war, but we all know how imperfect war is. We only have to look at recent history to remember that in modern war there is seldom a clear winner and the costs are staggering and tragic. Consider: Korean War: No winner emerged. Instead, Korea remains divided and the North retains the capability of making a nuclear bomb(s). The war was waged at a great cost in terms of money and lives. Vietnam War: Objectively, North Vietnam, the communists, achieved their goals of reuniting and gaining independence for the whole of Vietnam, and it remains under communist rule today. The U.S. dropped more than 7 million tons of bombs—more than twice the amount that was dropped on Europe and Asia in World War II—and we lost more than 58,000 young lives. Not a perfect solution or result. Gulf War: The aftermath of the Persian Gulf War appeared to be a victory, but what we learned is that the victory was hollow. Saddam Hussein was not forced from power and the region became less stable. Many believe that this war helped to make Al Qaeda a force that would later strike our homeland. Iraq War: The initial stage of the war was a raging success—the banner proclaimed “Mission Accomplished.” Yet, the war created eight years of sectarian violence, 4,900 American lives lost and many more severely injured, and it amounted to a trillion dollar debt from which we still haven’t recovered. Iraq is still incapable of defending itself, and it gave rise to ISIS. We need to ask ourselves if an imperfect agreement that may produce peace and diminish the potential of a nuclear Middle East is a better risk than the alternatives. Or are we willing to put our country and the world at risk by pursuing alternatives that have a dismal and tragic record. Can we afford to risk isolating ourselves from our allies, countries critical to solving the world’s most urgent problems? Are we willing to once again shed the blood of our youth by waging war? Writer Archibald McLeish said, “There is only one thing more painful than learning from experience and that is not learning from experience.” We have a clear choice. The Iran Nuclear Agreement has risks, but experience has shown that the alternatives are much more costly in terms of world standing, capital and human lives. All our options are imperfect and risky, but the greater risk here is repeating the past when we have a chance to take a risk for peace instead.  Have you been in a near-miss human collision recently? This seems to be happening to me more frequently these days. When it happens, I’m typically in an airport, at a mall, or on a sidewalk, and notice I’m on a collision course with another person absorbed in their smart phone. Not wanting to create a scene or cause harm to myself or the other person, I change course. As I do, the other person notices my movement and momentarily looks away from their phone, only to reengage, heading toward the next collision. These incidents got me thinking about our extraordinary capacity to notice. We humans have been blessed with five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste, which help us to fully experience and understand our presence in and connection to the space we occupy. History, anthropology, and other sciences validate that human survival was based to great extent on our ability to notice when we were in danger and when we were safe. Noticing and then avoiding danger allowed us to flourish. Noticing is still a significant factor in our safety, engagement with work and life, and survival. It matters if you notice that you are about to collide with a fellow citizen as you’re walking. It matters if you notice that your child is sad. It matters if you notice a bicyclist is sharing your road. It matters if you notice a co-worker is using a ladder that is not tied off or has not locked out an energy source before working to fix the problem. And it matters, as a leader, if your employees are happy and engaged or frustrated and on autopilot. There is no doubt in my mind that using our senses to notice creates advantages, improves our safety and engagement, and generates a fuller understanding of our world. This exceptional capacity that can provide so many benefits, however, is being threatened by our technology, self-absorption, and isolation from the experiences of those around us. Each time we turn off our capacity to notice, we become vulnerable. When we become so self-absorbed we don’t notice the homeless person in the shadows, or isolate and embed ourselves so deeply in our homogenous groups we don’t notice social injustice and inequality, we become vulnerable. We are vulnerable because we’ve loss the opportunity to connect and understand. Our five senses are pathways into our hearts and minds, where our shared human experiences are stored. If we miss the opportunity to notice, we miss the opportunity to understand, connect, and make a difference in the lives of others and ourselves. To be and feel noticed meets a deep human need. Have you ever longed to be noticed by someone, maybe a teacher, a coach, a parent, or a boss? When that moment of being noticed happens, you are infused with good feelings. If you feel unnoticed, unpleasant feelings and actions arise. Children misbehave when they go unnoticed, and workers languish and under-perform. Recently, our country has experienced riots and demonstrations by people struggling to have their plight noticed. Noticing is a powerful capacity we all possess, and it offers wonderful things. It can change a friendship or a working relationship—it can change the world. It is a gift to notice someone, and especially to oneself, because you are now more present and in tune with your world. What we notice and don’t notice defines who we are in that moment as well as provides us the opportunity for change. Noticing can be uncomfortable and exhilarating. The act of noticing will open you up to your sixth sense (s) - your emotions. You may notice that you are feeling sadness or anger or joy and awe depending on what you are experiencing. Emotions increase the power of noticing by adding clarity and texture. Martin Luther King said, “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” I like to paraphrase his quote to say that our lives begin to end when we lose our ability to notice the things that matter.  Normally, you assess an organization’s safety culture by observing how employees translate the company’s principles, values, attitudes, and goals into their behavior and decision-making. This seems like a pretty straightforward method, but beware of drawing conclusions based only on observations—you’ll fall into the assumptions trap. I’ve fallen into this myself by relying on direct observations and reports consisting of data based on observations, and I suspect I am not alone. The assumptions trap is a consequence of the way in which the human brain forms patterns to help us manage a complicated life more efficiently. Patterns feed our assumptions. They help us react, predict and make decisions regarding situations without having to assemble and sift through all of the details of what we are observing. The problem is the brain has no investment in making distinctions between fact and fiction. It takes in what it sees, dismisses what doesn’t fit, and draws a conclusion as expeditiously as possible. It will even add in data to fill any gaps just to complete the picture to fit the established pattern. This works very well when we need to slam on the brakes to avoid a child who darts into the road. However, this process has limits when used exclusively to assess or make assumptions about the effectiveness of a safety culture. David McLean, Chief Operating Officer for Maersk, expressed this realization in his article “The Importance Of Process Safety & Promoting A Culture of PSM.” “We were all very good at measuring personal safety performance, i.e. slips, trips, and falls, and this is very tangible, but did a good personal safety record mean we had a safe operation? Clearly not, as several major accidents had proven.” Avoid the Assumptions Trap by Engaging in Conversations “Can you hear me now?” was the key refrain from a Verizon commercial a few years ago. If you listen, you can hear employees using this same refrain in regard to their relationship with their managers. “They never listen to us, and when they do, they don’t hear what we are saying,” I’ve heard employees say. “They already have their minds made up.” Consider for a moment that managers spend 75% to 90% of their time in conversations! Who are they having these conversations with? And are they really listening or just filling in the gaps of existing beliefs and patterns? To understand and know one’s culture you must listen to it—not just to the words but also to the emotional texture of the words. A safety culture is created, nurtured and sustained by the breath and quality of the conversations that take place and the ones that don’t. “What people say and what they withhold matters,” said David Arella, founder and CEO of 4Spires. “Language trumps control. How the communication is initiated and conducted is often more important than what is communicated. An organization is a network of person-to-person work conversations during which information and energy is exchanged. Like cells in your body, the quality of these work-atoms determines the effectiveness of the whole. Attending to and influencing work conversations can help transform culture and improve collaboration.” The true nature of a culture is revealed through its conversations. If you want to understand your culture before making assumptions about your culture’s strengths and weaknesses—what motivates employees and what’s in their hearts and minds—you must engage in open and honest talk. Conversations can help give meaning to observations. Culture is made up of layers of conversations that are constantly vibrating and emitting information. Learning to notice and listen to these waves of information is a critical culture competency. It requires that leaders be committed to moving through the casual and superficial noise in order to gain insight into the organization’s authentic culture and discern what is really motivating employee performance. Don’t Use Data: How to assess your safety culture more effectively Edgar H. Schein, PhD, considered to be one of the foremost experts on organizational culture, believes that if you want to access your organization’s culture, bring together a group of employees who represent each part of the organization and provide an opportunity for them to dialogue about their issues, concerns, and the strengths and weaknesses they experience and perceive in the safety culture. Here is a simple but effective model to help organizations assess and transform their safety culture. It calls for leaders, managers, supervisors, and employees to engage in authentic conversations in which each can express and share their concerns and build the trust required to move forward. Leaders frequently expressed that they had reservations about engaging in these conversations, particularly those that reached below the surface. They preferred to use a survey (hard data). But after working with this model, not only did they obtain the data they wanted; they gained the commitment they needed from employees to work toward common goals. The following questions can help assess if your have a culture that values conversations or if it is reliant on assumptions and patterns. · Is it like pulling teeth to get employees to talk in meetings? · How often do safety leaders practice walking and talking about the site? · Is the word stupid—or a similar insult—ever used to describe safety incidents or the employee involved? · What emotion(s) best describes the mood of the safety culture? Frustration, boredom, disappointment—or excitement, curiosity, and passion? · Do managers abhor meetings and feel that they are a waste of time? · How often have employee safety recommendations been implemented? This self-assessment will begin to give you an indication if the conditions of your safety culture are conducive to meaningful dialogue; if it encourages open and honest conversations or stifles it. A word of caution though: Just because employees may be reluctant to engage in conversations doesn’t mean they don’t want to be heard. Their behavior may be more about their lack of trust, fear of blame, or a result of previous conversations that resulted in a negative experience. A positive safety culture is a repeatedly observant one, not just of behavior but also of its tone and content. Safety leaders would be well served to develop a practice of deeply listening and observing before making assessments and judgments. Contact Tom Wojick for more information on how to introduce conversations into your culture 401-525-0309 [email protected]  A familiar and popular business performance metric is ROI—Return on Investment. For many, this is the keystone of workplace culture, driving business strategy and decisions as well as the behavior of managers and employees. Most businesses won’t invest capital or other resources unless there is a direct positive financial gain from the investment. It’s a no brainer—if a business wants to be successful and remain viable, it must generate a return. But is there a dark side to ROI? Balancing ROI and ROS There is a performance metric that is as critical to organizational success as ROI: ROS—Return on Safety. Providing a healthy balance to ROI, ROS (#returnonsafety) is a metric that applies to every business, though it carries particular significance in manufacturing and production industries such as oil and gas, transportation, chemical, farming, and recycling. In these workplaces, humans interact closely with heavy machinery and hazardous substances, and it is not an unproven theory that focusing too intently on ROI can affect employee safety and decisions as well as organizational success. In the last five years we’ve witnessed tragedies that serve as prime examples of what happens when organizations’ focus on ROI is dominant: Upper Big Branch Mine (29 miners killed): A final report on the West Virginia tragedy indicated that Massey Energy had a culture of willful disregard for safety in favor of optimized profit and production. Deepwater Horizon drilling platform explosion (11 workers killed): A statement from the final report noted that “the culture of safety is less strong than the imperative to meet deadlines, what has been referred to in the Deepwater Report by the Center for Catastrophic Risk Management as an ‘imbalance between production and protection’” (Forbes.com, 11/28/2012). General Motors’ faulty ignition switch (31 deaths): Began with an ignition switch that was found to be defective in 2001. GM’s CEO, Mary Barra, stated to a congressional committee investigating the failure, "The customer and their safety are at the center of everything we do." Yet, GM’s own internal investigation, The Volukas Report, noted that there were conflicting messages regarding ROI and safety: “Two clear messages were consistently emphasized from the top: 1) ‘When safety is at issue, cost is irrelevant’ and 2) ‘Cost is everything.’” One engineer said that the emphasis on cost control at GM “permeates the fabric of the whole culture.” The Price of Imbalance The cost of these disasters combined is estimated to top 50 billion dollars. But the real tragedy is that as many as 71 people lost their lives because employee safety became an afterthought, or was never a priority to begin with. This is the dark side of ROI. Could a culture that focuses on ROS, instead, have prevented these disasters? Most experts and authorities say yes. Peter Kelly-Detwiler’s 2012 Forbes article, “BP Deepwater Horizon Arraignment: A Culture That ‘Forgot to be Afraid,’” addresses not just the Deepwater Horizon disaster but others as well: “The gist of all of these inquiries and reports is pretty much the same: repetition, complacency, complicated technology, and a poor culture of safety combined with the production/protection imbalance is a recipe for failure. This can generally be remedied by the appropriate focus on best available safety practices and technology.” Calculating the Worth of ROS ROS as a metric is not as easy to calculate as ROI. It doesn’t show up in quarterly profit and loss statements and if it does its typically as an expense, therefore organizations have difficulty assessing its value to the bottom line—something many CEOs, under pressure from shareholders and the financial markets, can’t see beyond. Instead, ROS requires leaders to have a vision that extends beyond quarterly reports. These men and women must have a steadfast commitment to safety, the courage to confront the short-term thinking of Wall Street, and a willingness to reject the idea that production and profit achieved at the expense of employee safety is a sustainable business strategy. Leaders who respect the value proposition of ROS understand how intimately safety is related to quality, reputation, efficiency, innovation, and worker engagement and loyalty. How One Company Benefitted Paul O’Neill, CEO of Alcoa from 1987-2000, was a leader who understood ROS and had the foresight to make it his keystone business philosophy and strategy. In “How Changing One Habit Helped Quintuple Alcoa’s Income,” Drake Baer writes: “The emphasis on safety made an impact. Over O'Neill's tenure, Alcoa dropped from 1.86 lost work days to injury per 100 workers to 0.2. By 2012, the rate had fallen to 0.125. “Surprisingly, that impact extended beyond worker health. One year after O'Neill's speech, the company's profits hit a record high. “Focusing on that one critical metric, or what (writer Charles) Duhigg refers to as a ‘keystone habit,’ created a change that rippled through the whole culture. Duhigg says the focus on worker safety led to an examination of an inefficient manufacturing process—one that made for suboptimal aluminum and danger for workers. “By changing the safety habits, O'Neill improved several processes in the organization. When he retired, 13 years later, Alcoa's annual net income was five times higher than when he started.” An ROS mindset instills organizational leaders with the compassion, courage, and values of a Paul O’Neill. To assess the balance and tension between ROI and ROS in your business, review the following list. 10 warning signs your culture is ROI-influenced: 1) The person who is responsible for safety does not report directly to the CEO 2) The CEO and managers rarely discuss safety at strategy, HR, production, quality, and sales and marketing meetings. 3) The company’s safety vision is not linked to the business strategy or worst it is non-existent. 4) Managers throughout the organization fail to consistently emphasize safety or are resistant to safety initiatives. 5) The organization has few if any feedback loops for continuous safety improvement. 6) Metrics used to evaluate individual and team performance have minimal to no weight placed on safety. 7) Employees are not familiar or are skeptical of the sincerity regarding the company’s safety vision and values. 8) Training and development do not emphasize safety. 9) New employees and contractors are not first and formally introduced and oriented to the organizations safety vision and values. 10) Employees are fearful of negative repercussions for reporting safety incidents, risks, and hazards. This is just the beginning though. Truly understanding what drives your business requires a more nuanced and careful approach than checking some boxes. I’ve seen many situations in which the person responsible for EHS reported directly to the CEO yet felt disrespected and undervalued, and vice versa. Assessing the motives of any organization requires a hard look at these relationships. Ultimately, an organization that creates a culture more heavily influenced by ROI than safety cannot ensure success for its shareholders or stakeholders. Choosing to gamble the health and wellbeing of employees for production and profit, these businesses will always be a risky—not reputable or ethical—investment. ROS-Return on Safety C The Renewal Group 2015 References and Acknowledgements: Volukas Report: http://www.autonews.com/article/20140605/OEM11/140609893/read-gms-internal-report-from-investigator-anton-valukas-here I want to acknowledge Hugo Moreno’s article, “10 Warning Signs of a Weak Culture of Quality” (Forbes Insight), which provided the basis for the checklist used in this article  I can’t seem to get through a page of John Gardner’s book Self-Renewal: The Individual and the Innovative Society—which is full of lessons, advice and wisdom on the nature and nurturing of self-renewal—without being struck by a concept that resonates deeply. The following is just one example: “For every citizen movement that changes the course of history, there are many thousands that hardly create a ripple. The few movements that survive are those that speak to the authentic concerns of substantial numbers of people.” Immediately, names like Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Susan B. Anthony, and Harvey Milk come to mind. These individuals were able to profoundly articulate the authentic human and civil rights concerns of millions of disaffected people, and because of this they became leaders within movements that changed societies. The ability to sense, understand and authentically communicate the concerns of others is the core of leadership, and it’s as important in leading organizations as it is in large-scale societal change, because at the heart of all workplaces are people with concerns. An alternative perspective on engagement Organizations that achieve high levels of employee engagement experience superior results in many critical performance and success metrics, including revenue. And yet for many leaders, engendering deep levels of stakeholder engagement appears to be a difficult challenge. Too often I’ve heard leadership teams, when considering an engagement effort, say, “You can never satisfy them; if we change, they’ll only find something else to complain about.” This perspective of engagement, about giving in or giving up something, is a formula for failure. An alternative perspective that I recommend to leaders is to frame engagement as a “concern movement”: a process of recognizing and attending to the mutual concerns of both management and employees. The foundation of a concern movement In his book Moral Courage, Rushworth Kidder identifies the values of honesty, responsibility, respect, fairness, and compassion as core human values. The foundation of a concern movement starts with a focus on these five universally accepted values, which, when invoked and practiced by leaders, speak to the essence of human concerns. Honesty, responsibility, respect, fairness, and compassion transcend all cultural and organizational demographics. When they flourish, so does human engagement. To build a culture of engagement, organizations must integrate these values into the “why” and “how” they lead and the structures and systems of their operation. This approach doesn’t require a leader to be a great orator, or to risks one’s safety for a movement—but it does require that you recognize and understand your stakeholders’ concerns and to be able to authentically resonate with their concerns. Values are the powerful “why” that influence what people do and how they do it. Try delivering bad news to your organization without respect and compassion; it will inflame passions, kill engagement, or both. When employees perceive their organization to have a disregard for basic human values, it takes a toll on organizational results. On the other hand, the benefits of employee engagement are well documented, and the road to engagement is paved with core human values. Organizations willing to walk the walk and talk the talk and start their own concern movement will succeed—both personally and as a whole. |

Follow us

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed