This seems like a pretty straightforward method, but beware of drawing conclusions based only on observations—you’ll fall into the assumptions trap.

I’ve fallen into this myself by relying on direct observations and reports consisting of data based on observations, and I suspect I am not alone. The assumptions trap is a consequence of the way in which the human brain forms patterns to help us manage a complicated life more efficiently.

Patterns feed our assumptions. They help us react, predict and make decisions regarding situations without having to assemble and sift through all of the details of what we are observing. The problem is the brain has no investment in making distinctions between fact and fiction. It takes in what it sees, dismisses what doesn’t fit, and draws a conclusion as expeditiously as possible. It will even add in data to fill any gaps just to complete the picture to fit the established pattern. This works very well when we need to slam on the brakes to avoid a child who darts into the road. However, this process has limits when used exclusively to assess or make assumptions about the effectiveness of a safety culture.

David McLean, Chief Operating Officer for Maersk, expressed this realization in his article “The Importance Of Process Safety & Promoting A Culture of PSM.”

“We were all very good at measuring personal safety performance, i.e. slips, trips, and falls, and this is very tangible, but did a good personal safety record mean we had a safe operation? Clearly not, as several major accidents had proven.”

Avoid the Assumptions Trap by Engaging in Conversations

“Can you hear me now?” was the key refrain from a Verizon commercial a few years ago. If you listen, you can hear employees using this same refrain in regard to their relationship with their managers.

“They never listen to us, and when they do, they don’t hear what we are saying,” I’ve heard employees say. “They already have their minds made up.”

Consider for a moment that managers spend 75% to 90% of their time in conversations! Who are they having these conversations with? And are they really listening or just filling in the gaps of existing beliefs and patterns? To understand and know one’s culture you must listen to it—not just to the words but also to the emotional texture of the words. A safety culture is created, nurtured and sustained by the breath and quality of the conversations that take place and the ones that don’t.

“What people say and what they withhold matters,” said David Arella, founder and CEO of 4Spires. “Language trumps control. How the communication is initiated and conducted is often more important than what is communicated. An organization is a network of person-to-person work conversations during which information and energy is exchanged. Like cells in your body, the quality of these work-atoms determines the effectiveness of the whole. Attending to and influencing work conversations can help transform culture and improve collaboration.”

The true nature of a culture is revealed through its conversations. If you want to understand your culture before making assumptions about your culture’s strengths and weaknesses—what motivates employees and what’s in their hearts and minds—you must engage in open and honest talk. Conversations can help give meaning to observations.

Culture is made up of layers of conversations that are constantly vibrating and emitting information. Learning to notice and listen to these waves of information is a critical culture competency. It requires that leaders be committed to moving through the casual and superficial noise in order to gain insight into the organization’s authentic culture and discern what is really motivating employee performance.

Don’t Use Data: How to assess your safety culture more effectively

Edgar H. Schein, PhD, considered to be one of the foremost experts on organizational culture, believes that if you want to access your organization’s culture, bring together a group of employees who represent each part of the organization and provide an opportunity for them to dialogue about their issues, concerns, and the strengths and weaknesses they experience and perceive in the safety culture.

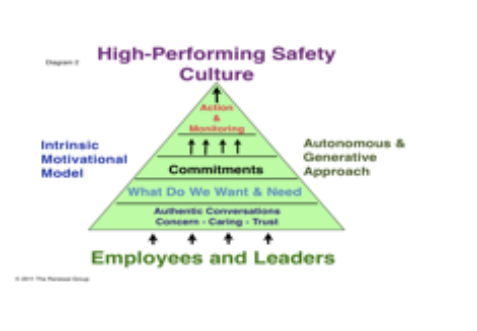

Here is a simple but effective model to help organizations assess and transform their safety culture. It calls for leaders, managers, supervisors, and employees to engage in authentic conversations in which each can express and share their concerns and build the trust required to move forward.

Leaders frequently expressed that they had reservations about engaging in these conversations, particularly those that reached below the surface. They preferred to use a survey (hard data). But after working with this model, not only did they obtain the data they wanted; they gained the commitment they needed from employees to work toward common goals.

The following questions can help assess if your have a culture that values conversations or if it is reliant on assumptions and patterns.

· Is it like pulling teeth to get employees to talk in meetings?

· How often do safety leaders practice walking and talking about the site?

· Is the word stupid—or a similar insult—ever used to describe safety incidents or the employee involved?

· What emotion(s) best describes the mood of the safety culture? Frustration, boredom, disappointment—or excitement, curiosity, and passion?

· Do managers abhor meetings and feel that they are a waste of time?

· How often have employee safety recommendations been implemented?

This self-assessment will begin to give you an indication if the conditions of your safety culture are conducive to meaningful dialogue; if it encourages open and honest conversations or stifles it.

A word of caution though: Just because employees may be reluctant to engage in conversations doesn’t mean they don’t want to be heard. Their behavior may be more about their lack of trust, fear of blame, or a result of previous conversations that resulted in a negative experience.

A positive safety culture is a repeatedly observant one, not just of behavior but also of its tone and content. Safety leaders would be well served to develop a practice of deeply listening and observing before making assessments and judgments.

Contact Tom Wojick for more information on how to introduce conversations into your culture

401-525-0309

[email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed